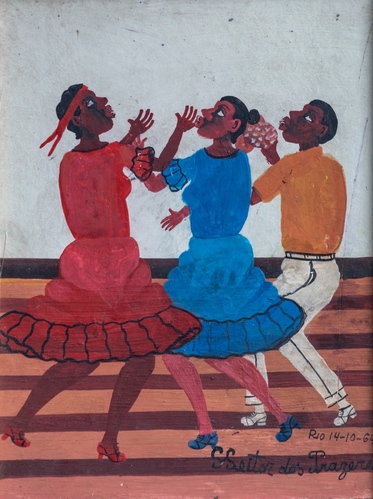

Heitor Dos Prazeres (1898-1966) was a samba musician and self-taught painter in Rio de Janeiro. Son of a military musician and a seamstress, he grew up surrounded by Rio’s Afro-Brazilian music scene which was dominated by carnival. In his late ’30’s he developed an interest in painting and started portraying the life and culture he observed in the streets of Rio’s favelas, including mulatas dancing, people in neighborhood bars, and scenes from the genres of carnival and Rio’s extravagant downtown entertainment district. By the 1950’s he was a known and celebrated “naif” artist whose works today are included in private and museum collections all over Brazil, and the subject of several books and catalogs.

Manuel Mendive Hoyo needs no introduction. We ourselves were long aware of this artist’s extraordinary body of work in the early 1990’s when we visited Havana during the notorious “special period”. He was already an internationally known artist then. Now, decades later, according to Wikipedia, “Manuel Mendive (born 1944) is one of the leading Afro-Cuban artists to emerge from the revolutionary period, and is considered by many to be the most important Cuban artist living today”.

During a recent trip to Havana we decided to visit Mendive’s little town, the sleepy, charming colonial village where he has made his home for most of his life.

Almost 20 years ago, during one of my visits to Salvador, Bahia, I came across an incredible, don’t know what to call it - carnival costume / wearable altar / art brut installation / outsider art assemblage. A dozen and a half years later I lent the piece to a spectacular exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City: When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego. The maker of this incredible work is Raimundo Borges Falcão, about whom not much is known. The exhibition produced a fabulous catalog. I wrote a page about Borges Falcão and his incredible work:

05/22/2018

José Francisco Borges (J. Borges) lives and works in Bezerros, Pernambuco, Brazil where he was born in 1935. He is a self-taught woodcarver, woodblock printer and poet who started as an itinerant peddler of home-made illustrated chapbooks addressing popular themes, folk tales and legends native to the impoverished Northeast (Sertão). This unique art form - "literatura de cordel" (string literature) - consists of written verses and woodblock prints illustrating the rhymed stories. Traditionally, the cordel booklets were sold at country fairs and rural markets where they hung from a piece of string or clothesline.

05/12/2018

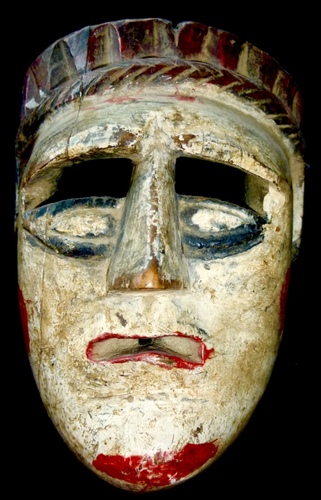

In the rural areas and villages of indigenous Guatemala, masks have long been an integral part of life, binding past and present with tradition, ritual and ceremony. For many generations, folk artists of Maya descent have skillfully carved elaborate masks from different woods, painted in various colors, to be used in choreographed dance dramas. The most apparent quality of Guatemalan masks is their diversity. Although the regional centers from which they originate may be only a few miles apart, the masks are unique and distinct.

One of the most important deities in the Yoruba pantheon of western Africa is Ogún, god of war and of ironworking, patron of blacksmiths and of all who use metal in their occupations. He continues to rule the spirit world of black cultures throughout Brazil and the Americas. Ogum (in Portuguese) embodies the transformative power and sacred role of iron and as such has given ritual blacksmiths (ferramenteiros) a magical gift.

I met Derek Webster by accident in 2001 when I got lost driving around South Chicago and made a wrong turn. It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

Each June, thousands of Ecuadorians flock to indigenous highland communities like the ancient village of Pujili in the Andean province of Cotopaxi. The occasion is Corpus Christi, a week-long, boisterous pageant whose highlight is the parade of El Danzante. This festival, celebrated throughout Ecuador’s highlands, is like no other, a joyous pagan ritual honoring sun and earth and harvests blended with Catholic elements.

Victor Teodoro Caceres was born in Tilcara in the Province of Jujuy, Argentina around 1940. His native region is a province in Argentina’s remote northwest populated by indigenous Quechua villages and surrounded by desert landscapes and stunning multi-colored rock formations. Spanish colonial traditions are very much alive there today, along with indigenous cults. For decades, Caceres worked diligently to adapt his town’s Semana Santa (Holy Week) ritual to his own ideas and transform it into something else altogether.