Carlos Garcia Huergo’s mysterious drawings combine images of human figures, birds or fantasy creatures with letters, names, numbers and mathematical and religious references. He thus creates a universe populated by inhabitants of his own inner environment which includes angels, devils and - always in the foreground - people, surrounded by text and mathematical symbols.

Almost 20 years ago, during one of my visits to Salvador, Bahia, I came across an incredible, don’t know what to call it - carnival costume / wearable altar / art brut installation / outsider art assemblage. A dozen and a half years later I lent the piece to a spectacular exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City: When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego. The maker of this incredible work is Raimundo Borges Falcão, about whom not much is known. The exhibition produced a fabulous catalog. I wrote a page about Borges Falcão and his incredible work:

05/05/2018

To tell the story about how we - that is Michael and I - became friends with Juan Roberto Diago Durruthy, commonly known as “Diago”, I have to tell it backwards.The last time we saw him in Havana, in January of 2017, Diago started reminiscing. How long had we known each other? More than a dozen years, and much had changed. Now that he is an international star in the contemporary art world, he is represented by major galleries, and his works are included in international museum collections and featured by leading auction houses.

I met Derek Webster by accident in 2001 when I got lost driving around South Chicago and made a wrong turn. It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

Each June, thousands of Ecuadorians flock to indigenous highland communities like the ancient village of Pujili in the Andean province of Cotopaxi. The occasion is Corpus Christi, a week-long, boisterous pageant whose highlight is the parade of El Danzante. This festival, celebrated throughout Ecuador’s highlands, is like no other, a joyous pagan ritual honoring sun and earth and harvests blended with Catholic elements.

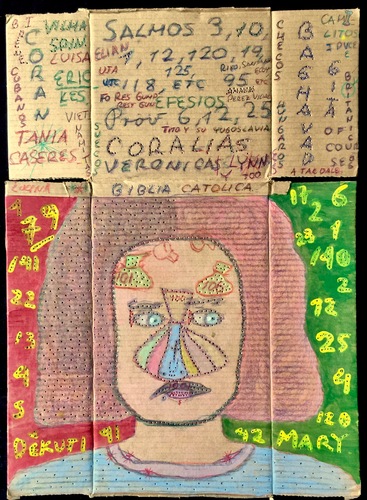

Victor Teodoro Caceres was born in Tilcara in the Province of Jujuy, Argentina around 1940. His native region is a province in Argentina’s remote northwest populated by indigenous Quechua villages and surrounded by desert landscapes and stunning multi-colored rock formations. Spanish colonial traditions are very much alive there today, along with indigenous cults. For decades, Caceres worked diligently to adapt his town’s Semana Santa (Holy Week) ritual to his own ideas and transform it into something else altogether.