Almost 20 years ago, during one of my visits to Salvador, Bahia, I came across an incredible, don’t know what to call it - carnival costume / wearable altar / art brut installation / outsider art assemblage. A dozen and a half years later I lent the piece to a spectacular exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City: When the Curtain Never Comes Down: Performance Art and the Alter Ego. The maker of this incredible work is Raimundo Borges Falcão, about whom not much is known. The exhibition produced a fabulous catalog. I wrote a page about Borges Falcão and his incredible work:

05/12/2018

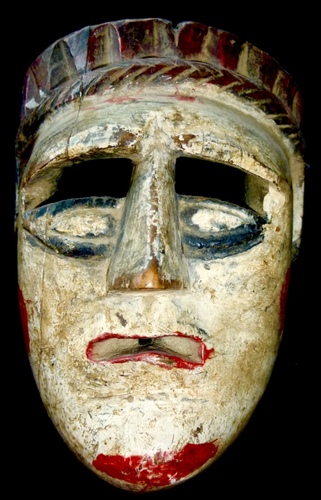

In the rural areas and villages of indigenous Guatemala, masks have long been an integral part of life, binding past and present with tradition, ritual and ceremony. For many generations, folk artists of Maya descent have skillfully carved elaborate masks from different woods, painted in various colors, to be used in choreographed dance dramas. The most apparent quality of Guatemalan masks is their diversity. Although the regional centers from which they originate may be only a few miles apart, the masks are unique and distinct.

Each June, thousands of Ecuadorians flock to indigenous highland communities like the ancient village of Pujili in the Andean province of Cotopaxi. The occasion is Corpus Christi, a week-long, boisterous pageant whose highlight is the parade of El Danzante. This festival, celebrated throughout Ecuador’s highlands, is like no other, a joyous pagan ritual honoring sun and earth and harvests blended with Catholic elements.