Manuel Mendive Hoyo needs no introduction. We ourselves were long aware of this artist’s extraordinary body of work in the early 1990’s when we visited Havana during the notorious “special period”. He was already an internationally known artist then. Now, decades later, according to Wikipedia, “Manuel Mendive (born 1944) is one of the leading Afro-Cuban artists to emerge from the revolutionary period, and is considered by many to be the most important Cuban artist living today”.

During a recent trip to Havana we decided to visit Mendive’s little town, the sleepy, charming colonial village where he has made his home for most of his life.

06/11/2018

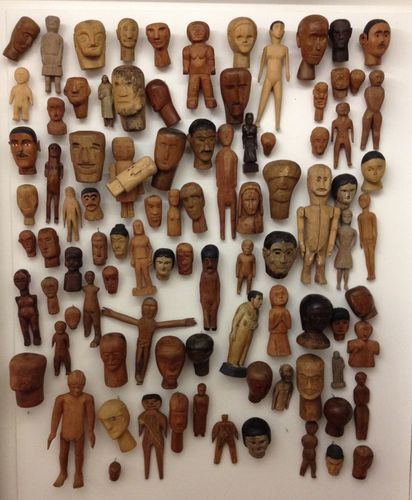

Brazilian ex-voto sculptures - wooden heads, torsos, body parts - represent a special art form without “artists”. Made for generations by anonymous creators, men and women from rural communities who were never exposed to the concepts of art, three-dimensional ex-votos are unique to Brazil’s Northeast (“Nordeste”) - a world synonymous with poverty and backwardness.

05/12/2018

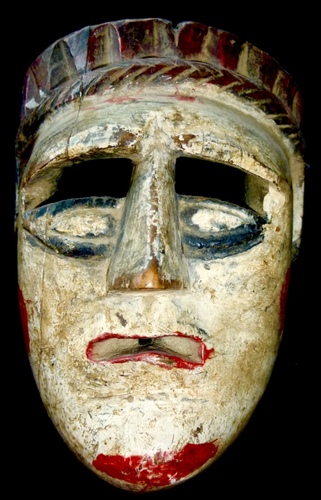

In the rural areas and villages of indigenous Guatemala, masks have long been an integral part of life, binding past and present with tradition, ritual and ceremony. For many generations, folk artists of Maya descent have skillfully carved elaborate masks from different woods, painted in various colors, to be used in choreographed dance dramas. The most apparent quality of Guatemalan masks is their diversity. Although the regional centers from which they originate may be only a few miles apart, the masks are unique and distinct.

Since a Papal visit to Cuba in 1998 forced the Castro government to undo its ban of religious practices, worshippers of all flavors were out in the open again, yet none more so than the adherents of the Yoruba based religion which, fused with Catholic elements, has been practiced widely in Afro-Caribbean regions since the beginning of trans-Atlantic slave trade. Santería, conducted in secrecy during much of the Cuban revolution, had started to bubble up to the surface again.

One of the most important deities in the Yoruba pantheon of western Africa is Ogún, god of war and of ironworking, patron of blacksmiths and of all who use metal in their occupations. He continues to rule the spirit world of black cultures throughout Brazil and the Americas. Ogum (in Portuguese) embodies the transformative power and sacred role of iron and as such has given ritual blacksmiths (ferramenteiros) a magical gift.

Each June, thousands of Ecuadorians flock to indigenous highland communities like the ancient village of Pujili in the Andean province of Cotopaxi. The occasion is Corpus Christi, a week-long, boisterous pageant whose highlight is the parade of El Danzante. This festival, celebrated throughout Ecuador’s highlands, is like no other, a joyous pagan ritual honoring sun and earth and harvests blended with Catholic elements.

Victor Teodoro Caceres was born in Tilcara in the Province of Jujuy, Argentina around 1940. His native region is a province in Argentina’s remote northwest populated by indigenous Quechua villages and surrounded by desert landscapes and stunning multi-colored rock formations. Spanish colonial traditions are very much alive there today, along with indigenous cults. For decades, Caceres worked diligently to adapt his town’s Semana Santa (Holy Week) ritual to his own ideas and transform it into something else altogether.